Timeline

1960 to 1970, Part I:

Exeter in a Changing World

By JEANNIE EOM, NOAH JAMES, STEPHEN MCNULTY and ANYA TANG

Editors and Staff Writers

Content Warning: Articles in this series depict specific instances of racial violence and aggression against Black and other non-white people. Racial epithets, though censored, are included.

This article is part of the multi-part series Since 1878, a project undertaken by the 142nd Board of The Exonian. The principal objective of this series is to examine the paper’s coverage of racism at the Academy and, by extension, in the country as a whole. This series will not provide a complete overview of racist events over the years in question. Additionally, research draws heavily from The Exonian’s archives, which present a biased depiction of racial dynamics at the Academy. Instead, the articles will offer a portrait of The Exonian, the Academy and the nation, decade by decade, by highlighting pieces published in the paper.

In Since 1878, The Exonian will follow the National Association for Black Journalists’ recommendations, referring to the n-word as [n-word], censoring n-gro in most contexts and capitalizing Black, in line with our updated style guide.

Regarding privacy, there are individuals named in these articles who are still alive today. Their statements represent their views as minors in the middle of their education. Most high schoolers do not write for publications like The Exonian, which archives every issue. The editors of the paper understand this unique situation and that views often change over time, particularly those held during high school. Additionally, every article represents more than its writer. Pieces in The Exonian go through editors and advisers, reflecting an institutional history.

However, Since 1878 uses their names to ground itself in the tangible and proximate. In Since 1878, the editors choose full transparency over perpetuating ambiguity and obscuring our history of racism.

During the 1960s, Rockingham County, New Hampshire experienced a population surge. Between 1950 and 1970, the county’s population nearly doubled. In fact, an op-ed published in The Exonian on May 29, 1968, described, “On Route 101-C, just south of Exeter, [was] a sign which boasted that ‘Rockingham County [was] the fastest growing county in America.’”

The county, which once hosted the Ku Klux Klan, did not host a sizable Black population. “Willfully or not, Rockingham County is almost completely segregated,” the article continued. The Academy, the piece noted, even more intensely reflected the county’s lack of diversity. Until the fall of 1968, Exeter had never had a Black faculty member.

Coverage

Local Area

The op-ed proceeded to argue for the appointment of Black employees at the Academy. “The Exeter N-gro,” it read, “has begun to recognize the obligation to help his ‘soul-brother’… Perhaps it should be brought to their attention that before they spread out to Roxbury or Harlem for a summer of social work, they can do considerable good for the community and their cause here in Exeter.”

The op-ed called for the Academy to “delay no longer in providing job opportunities to N-groes at every level” and urged Exeter students to take an active role in a community transformation such that Black Bostonians could “extricate themselves from the hopeless suffering of the slums.”

Segregationism and racism gripped the public discourse of New Hampshire throughout the 1960s, both in local daily conversation and the local press. An op-ed by anonymous student D. C. in The Exonian’s Oct. 6, 1962 issue, for instance, condemned a segregationist editorial in the Manchester Union-Leader written by publisher William Loeb. The Union-Leader’s piece, which began by noting, “The author of this editorial has black friends,” went on to argue, in full capitalization, that integration “IS THE OBJECTIVE, OF COURSE, WHICH THE COMMUNISTS SEEK. THEY WANT TO DESTROY ALL PRIVATE, PERSONAL FAMILY UNITS IN OUR SOCIETY, PLACING EVERYTHING UNDER THE DICTATORIAL CONTROL OF THE STATE.”

The piece in question drew considerable condemnation from then-Governor of New Hampshire, Wesley Powell, who had just lost a Senatorial primary. The editorial “was a disgrace to New Hampshire,” Powell said. D.C.’s op-ed offered several potential reasons for Gov. Powell’s recent loss in the Republican senatorial primaries—“his appointment of a Catholic to the Senate, his invitation to [Black people] to come to New Hampshire and publisher Loeb.”

Published May 22, 1968.

Black Enrollment

Over the course of the 1960s, Black enrollment at the Academy expanded significantly. A special issue of The Exonian called The New Black at Exeter, published on May 22, 1968, noted that from academic years 1959-60 to 1967-68, enrollment of Black students at Exeter expanded sixfold. Black students, however, remained significantly underrepresented at the Academy, as an anonymous student had critiqued in 1954. By 1968, Exeter had 38 Black students and constituted about five percent of the school population.

Despite this glaring underrepresentation, admissions officers at the Academy maintained that Exeter had equitable admissions practices. “Exeter has always had N-gro boys and we have always refused to regard the N-gro as inferior in any way,” Director of Admissions Charles M. Rice said. Asked to explain the minimal Black enrollment prior to the 1960s, Rice argued that “it was difficult to find qualified N-groes” until the founding of A Better Chance (ABC).

Rice, while emphasizing that “a Black applicant receive[d] the same treatment and [was] judged on the same merits as any other applicant,” also expressed concern as to whether Exeter could “rescue a boy from the ghetto and put him on a path towards a happy and prosperous future.”

“Frankly, many of our students are experiments,” Rice said.

A Better Chance and Special Urban Program

ABC was a program piloted at Dartmouth to increase enrollment of students from “educationally disadvantaged” neighborhoods. According to an article published in The Exonian on Feb. 8, 1964, Exeter chose to develop its own ABC program instead of joining the thirty preparatory schools invited to Dartmouth’s program. Under Exeter’s ABC plan, fifteen students of requisite background were to be enrolled in the Summer School, with the hopes that it would prepare them for eventually applying to the Academy.

The article also noted that, “although the Summer School report did not mention specifically the word ‘N-gro’ (the report called for ‘educationally disadvantaged’ students), the program is aimed primarily at the integration problem.”

By 1969, ABC had become a full-fledged, national organization. An article published Feb. 26, 1969, explored Exeter’s collaboration with ABC. “‘ABC’ gives young people from low-income families an opportunity to receive a good education in a leading boarding school or public high school,” The Exonian reported. “Aided by funds from 60 corporations and foundations, ‘ABC’ seeks out prospective candidates for 110 participating schools and finances summer programs at several colleges to help the chosen students adjust to their future educational and social environments. The expense of hiring teachers for the summer sessions falls entirely upon the funds solicited by the new Development Office of ‘ABC.’ In 1968, the office raised the money to help place 250 students in boarding schools.”

The article noted that likely candidates for Exeter were sent by ABC to then-Director of Admissions Charles M. Rice. Those accepted then spent their summer at Dartmouth or Williams College for an extended summer program. “Mr. Rice commented that ‘ABC’ has been working very successfully here at Exeter,” the article continued.

Then-upper Jonnie Tillman spoke positively of ABC in The Exonian. “The summer program showed me what it was going to be like here. Without it, I probably would have been totally ignorant of the situation at Exeter,” he said. “[It was] one of the greatest things that has happened to me.”

Several other organizations shared ABC’s mission of providing greater access to underprivileged students, including Exeter’s Special Urban Program (SPUR), which offered $13,000 in scholarships towards twenty students at Exeter’s Summer School. The Exonian reported that, “in an effort to contribute to the War on Poverty,” the Academy would pay for the Summer School tuition of select “N-gro and white boys and girls from Atlanta, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis high schools.” The Exonian claimed that the scholarship students had “low or average IQs,” and SPUR students engaged in a different math curriculum than non-SPUR students.

Roxbury Exchange Program

In 1962, the Academy arranged for an exchange program between Exonians and young students from historically Black neighborhood Roxbury, Massachusetts. The program was established through Father Cornelius Hatie ’48’s home parish in the town. The Exonian reported that the program was started to reduce “delinquency” among the Roxbury students.

“Delinquency among N-groes is high; Father Hastie feels that this is because they are unwanted by their neighbors since they are thought to drag down the level of the community,” The Exonian wrote. “[Myron Magnet said,] ‘If we make friends with them, friendship implies some sort of respect. Exeter’s intellectual life will rub off on them, and they will no longer consider ‘intellectual’ a dirty or unmasculine word.’”

The exchange program continued through the spring of 1962. That year, two Black students from Roxbury visited Exeter’s campus, and Exonians visited Roxbury and stayed with Black families.

The program expanded to include student service. The Exonian reported on the perceived benefits not solely to the Roxbury students, but also to Exeter students. “Perhaps by an exposure, through friendship, to something other than the gang fights and pool halls of their day-to-day existence, some of these boys will gain something,” The Exonian wrote. “Under the new student service proposal, Exeter students will appear, angels from the sky, to spend a week-end working on a Community Center. They will be the patricians, condescending out of pity to help the less fortunate.”

The Exonian noted a “selfish” purpose to the exchange as well. “The Exeter student, coming as he generally does from a professional, middle-class family,” the paper wrote in an Oct. 3, 1962 issue, “has never experienced the poor, hopeless, unwanted life that most of the boys in Father Hastie’s parish lived.”

The program continued throughout the decade—Exeter students would go to Roxbury on Wednesday afternoons, have dinner at Harvard and return by 8p.m. Reporting on the program’s success in 1967, The Exonian said, “Besides working well with children, the boys got a firsthand look at the urban situation and an opportunity to mingle with people from a different part of society.”

One student involved in the program, Lincoln Caplan II ’68, took to the pages of The Exonian to share a more nuanced experience. “The [Black] children constantly reminded me of my racial difference,” Caplan wrote while reflecting on his experience. “I was often asked by one skeptical boy how much I was getting paid to spend time with him.”

He added concern that, for some of his classmates, the experience was ingenuine. “Some whites I saw did not help anyone while tutoring in Boston’s South End,” he said. “These people only succeeded in ‘cleansing their souls’ because they thought they were giving by spending their time with N-gro children.”

Civil Rights Movement

In the searchable archives, Martin Luther King, Jr. did not appear before 1968. The paper devoted little coverage to King or the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s.

However, Exeter invited lecturers to the Academy to speak on civil rights. For instance, alumnus Larry Palmer ’62 spoke to Exonians in 1963 about the changing nature of the Civil Rights Movement. The Exonian reported on his lecture on Nov. 6, 1963 in an article entitled “Washington Rights March 'A Failure' Asserts Herods Speaker Palmer ’62.”

“Over the years the trend of thinking among most N-groes has been that of assimilation… The [National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peoples (NAACP)] advances this assimilation in its constant mish for integration,” The Exonian wrote. “But the new trend is toward nationalism, the ‘Back to Africa’ policy endorsed by the Black Muslims in their drive for separation of whites and blacks.”

“We are definitely against the present government,” Palmer said. “The N-gro today wants to do something so that a man like Kennedy cannot get into office, make the assertions he has, and then not fulfill them.”

Palmer commented on the movement away from methods of passive resistance and towards violent protest. “We are getting further and further away from ‘Non-Violence.’ Now Martin Luther King is about the only leader left who supports this theory,” Palmer said. “Prejudice is not a very rational thing. If you’re going to have violence, it might as well be directive.”

The Exonian also featured differing perspectives on race and assimilation, including arguments in favor of assimilationism. “In recent weeks,” one 1968 Letter to the Editor read, “I have become alarmed at the call for a reverse segregation movement by my fellow sold brothers here… This myth states that by definition integration is the uniting of an inferior substance (N-groes) with a superior substance (whites) in order to form useful substances (whites and N-groes who act like whites).”

“First of all I would like to say that this definition is false,” the piece continued. “Even if one excludes these parentheses and their contents one cannot find this definition in any reputable dictionary… The word therefore carries no shameful denotations, but only the ugly connotations which individuals harbor in their warped minds.”

“While I do not demand the White man’s love, I will demand that he respect me, or at least fake it,” the letter read.

The letter concluded with a call for moving away from revolt. “My very presence in the Academy indicates my acceptance of the values of White American society,” the letter’s author wrote. “This does not mean that I consider things to be as they should be, but [that] much more can be accomplished by reform than by revolt.”

Revolt continued to be a subject of focus on campus that year, particularly following an address provided by Special Visiting Fellow Robert D. Storey ’54. “With more than forty per cent of the N-gro population in the United States officially classed as ‘poor,’ and with N-groes keenly aware of their poverty, Mr. Storey thought it ‘no surprise that they burn buildings and loot stores,’” The Exonian reported.

The article featured Storey’s advocacy for combating unemployment among Black Americans as the perceived solution to unrest. “He went on to emphasize the need for the nation’s cities to provide training as well as employment opportunities for the great mass of jobless N-groes,” The Exonian wrote.

“A leader of a large city doesn’t have to be a N-gro, but this is the kind of mayor every city should have,” Storey said. “You must have a person who can bridge the white and black communities, not a person who will take a side.”

In 1969, coverage continued to focus on the changing nature of the Civil Rights Movement. Visiting Rev. John T. Walker spoke with Exonians on the role of the church in civil rights, along with the interactions of class and race. “Talking about his experiences, [Walker] told of the ‘stigma of the middle-class Black’ which confronted him when he first worked in the ghetto,” The Exonian wrote. “Most Blacks there, he said, distrusted him because of his image as a representative of the ‘Establishment’ church.”

“Rev. Walker’s tone became pessimistic when the Church’s future part in active social change was discussed,” The Exonian reported. “He said that the church would play ‘a very small role’ because its constituents have, for the most part, fired and threatened all of its outspoken clergymen.”

Walker emphasized the significance of personal sacrifice to further the nationwide Civil Rights Movement. Walker stated, “The clergy of the future must be willing to ‘lose their jobs and lives’ in order to procure an effective Church [for civil rights].”

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, the Academy mourned the civil rights leader and celebrated his legacy. Memorial services were held by the Afro-Exonian Society (later renamed the Afro-Latinx Exonian Society), by the school minister Rev. Edward S. Gleason in Phillips Church and by the Congregational Church.

Six days after Dr. King’s murder, the April 10 issue of The Exonian quoted a statement by Principal Richard W. Day, the chairman of the New Hampshire Commission for Human Rights, that was radio broadcast across the state. “A heavy and pressing responsibility falls on all of us as citizens of New Hampshire to insure that in this state and throughout the nation the principles for which [Dr. King] lived will continue to live,” he said. “We must reaffirm by every action our support of nonviolent response to the violent problems of our age and our determination that his dream of a free America shall become a reality.”

When Day was later asked whether there was a “racial problem” in New Hampshire, he responded, “At this moment I would say that there is no problem and there are great problems. I hope one of the benefits of this will be a sharpening of the sensitivities of this state.”

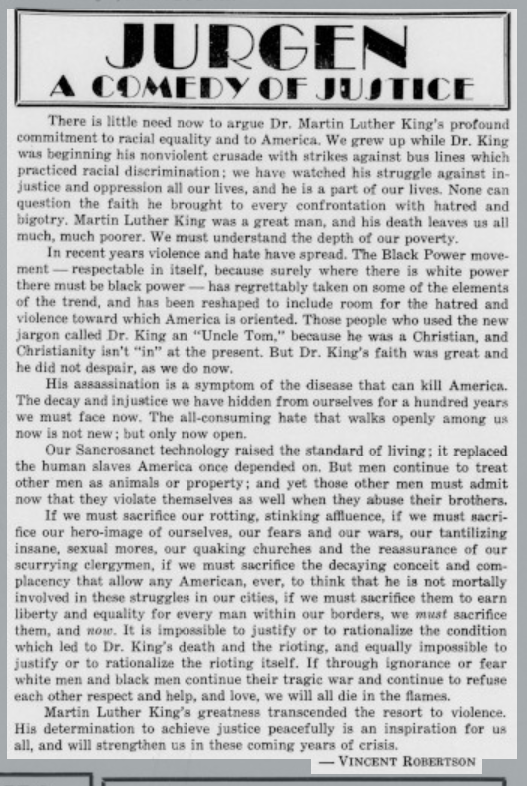

The April 10 issue also featured a submission by senior Vincent Robertson ’68. It is republished here in part:

There is little need now to argue Dr. Martin Luther' King’s profound commitment to racial equality and to America. We grew up while Dr. King was beginning his nonviolent crusade with strikes against bus lines which practiced racial discrimination; we have watched his struggle against injustice and oppression all our lives, and he is a part of our lives. None can question the faith he brought to every confrontation with hatred and bigotry. Martin Luther King was a great man, and his death leaves us all much, much poorer. We must understand the depth of our poverty.

In recent years violence and hate have spread. The Black Power movement respectable in itself, because surely where there is white power there must be black power has regrettably taken on some of the elements of the trend, and has been reshaped to include room for the hatred and violence toward which America is oriented.

His assassination is a symptom of the disease that can kill America. The decay and injustice we have hidden from ourselves for a hundred years we must face now. The all-consuming hate that walks openly among us now is not new; but only now open.

Our Sacrosanct technology raised the standard of living; it replaced the human slaves America once depended on. But men continue to treat other men as animals or property; and yet those other men must admit now that they violate themselves as well when they abuse their brothers.

If we must sacrifice our rotting, stinking affluence, if we must sacrifice our hero-image of ourselves, our fears and our wars, our tantalizing insane, sexual mores, our quaking churches and the reassurance of our scurrying clergymen, if we must sacrifice the decaying conceit and complacency that allow any American, ever, to think that he is not mortally involved in these struggles in our cities, if we must sacrifice them to earn liberty and equality for every man within our borders, we must sacrifice them, and now. It is impossible to justify or to rationalize the condition which led to Dr. King’s death and the rioting, and equally impossible to justify or to rationalize the rioting itself. If through ignorance or fear white men and black men continue their tragic war and continue to refuse each other respect and help, and love, we will all die in the flames.

Martin Luther King’s greatness transcended the resort to violence. His determination to achieve justice peacefully is an inspiration for us all, and will strengthen us in these coming years of crisis.

Published April 10, 1968.

The Exonian’s pages, and campus dialogue more broadly, reflected the continued racial upheaval of the 1960s. They reflected a key tension in Exeter’s history—that of a historically exclusive institution grappling with a push to include Black lives into spaces which had never truly included them.

Beyond integration, Black activists demanded respect for their voices, cultural traditions and human dignity. Part II of Since 1878’s 1960s issue focuses on this movement on Exeter’s campus through the lens of its new Afro-Exonian Society and the activists like Thee Smith ‘69 that created it.