Timeline

1970 to 1980

By ATHENA WANG and CLARK WU

Staff Writers

Content Warning: Articles in this series depict specific instances of racial violence and aggression against Black and other non-white people. Racial epithets, though censored, are included.

This article is part of the multi-part series Since 1878, a project undertaken by the 142nd Board of The Exonian. The principal objective of this series is to examine the paper’s coverage of racism at the Academy and, by extension, in the country as a whole. This series will not provide a complete overview of racist events over the years in question. Additionally, research draws heavily from The Exonian’s archives, which present a biased depiction of racial dynamics at the Academy. Instead, the articles will offer a portrait of The Exonian, the Academy and the nation, decade by decade, by highlighting pieces published in the paper.

In Since 1878, The Exonian will follow the National Association for Black Journalists’ recommendations, referring to the n-word as [n-word], censoring n-gro in most contexts and capitalizing Black, in line with our updated style guide.

Regarding privacy, there are individuals named in these articles who are still alive today. Their statements represent their views as minors in the middle of their education. Most high schoolers do not write for publications like The Exonian, which archives every issue. The editors of the paper understand this unique situation and that views often change over time, particularly those held during high school. Additionally, every article represents more than its writer. Pieces in The Exonian go through editors and advisers, reflecting an institutional history.

However, Since 1878 uses their names to ground itself in the tangible and proximate. In Since 1878, the editors choose full transparency over perpetuating ambiguity and obscuring our history of racism.

“Halloween at Exeter was celebrated with more spirit than the students seem to have been capable of these past few weeks,” The Exonian wrote on Nov. 1, 1977. While students had many costume ideas, some appeared multiple times. “In several cases, more than one student had the same idea. [Two Exonians] both claimed to be sheep, but an observer would have to squint hard to see the resemblance. There were at least two ‘Italian Stallions,’ a few ladies of the evening and scores of KKK members.”

Such an image would not have been new to the Academy or its surrounding environment. The Klan was about to experience a resurgence in the town of Exeter, which would continue into the 1980s and 1990s. Additionally, degradation of Black students by town residents persisted during the seventies. “It wasn’t until I reached the ‘wilds’ of New Hampshire, wrote Sheila Perry ’74, “that I was called a ‘spook’ or a “d-rkle’ by white people who sat sheltered in the security of their cars. Sometimes in the stores in town, I meet merchants who employ a harsh or indifferent tone in their dealings with me.”

The seventies continued the massive racial upheaval—in Exeter and beyond—sparked by the Civil Rights Movement. Exonians of the time grappled with the continued rise and activism of the AES, protests at home over the Vietnam War, a War on Drugs that disproportionately impacted Black lives and other mass movements that shaped young Americans in particular. They were also marked, in large part, by backlash to this activism. Exeter was no exception.

Coverage

A Better Chance and Black Enrollment

Established in 1964, the national organization A Better Chance (ABC) developed in the 1970s into “perhaps Exeter’s most consistent source of black candidates,” according to an article in The Exonian published June 5, 1971. At the time, the article noted, nineteen students enrolled at Exeter in the 1970-71 school year participated in ABC. The next year, The Exonian reported that 29 Exonians were enrolled in the Academy through ABC.

The same article provided a clearer picture of ABC’s role in independent school admissions. “A.B.C. is essentially a placement service for qualified students whose superior potentials are apparent, but whose academic work has been stifled by their environment. It consists of boys of all races, and competition for admission to the program is very steep. Once accepted into A.B.C., however, the student is virtually assured of admission to some independent school,” The Exonian wrote.

That article noted that ABC found recruiting Black students to be difficult. “Among the problems which the admissions office encounters in their efforts to solicit applications is the alienation which many blacks fear will exist at Exeter,” The Exonian wrote. “The feeling that they will be ‘deserting the struggle’ by coming to a well-off place such as PEA cannot really be overcome or set aside.”

Under the Nixon Administration, however, ABC and its peer programs lost significant federal funding. “The Johnson Administration invested huge sums of money for minority scholarships,” Principal Stephen G. Kurtz explained. “True, there was a great deal of waste and corruption, but, nonetheless, the money flowed into the ABC program. The financial situation has changed dramatically for the worse during the past seven years or so.”

ABC and its peer programs also faced controversy following the Supreme Court ruling in Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke (1977), which outlawed racial quotas in educational institutions. The Academy at the time had reserved ten seats for students from ABC, though The Exonian noted that this was not a racial quota, as ABC did not solely work with minority students.

Dean of the Academy Donald Cole was quick to note that the Academy’s efforts to recruit “underprivileged” students did not constitute affirmative action. ‘‘One must be careful to distinguish between ‘affirmative action’ and Exeter’s policy,” Cole said. “We do go out and recruit underprivileged students but we have no government contract in regards to quotas. This would be the case under the Affirmative Action Program.”

“The Academy cannot have an Affirmative Action Program,” Cole added. “Since quotas for minorities really amount to reverse discrimination.””

Debates about the merits of affirmative action programs also played into campus dialogue through the 1970s. Tony Gardner ’81 expressed his dissatisfaction with a solution that discriminates against “perfectly innocent people that happen not to belong to a minority” and “portions of society that have received good treatment and that have led profitable lives.”

“But do two wrongs make a right? Throwing the blame for the state of blacks on today’s young whites is parallel to blaming the young people of Germany for Hitler’s atrocities even when they had no part in it... Let us not tamper with the concept of equality for all, a concept which all of us hold dear,” Gardner wrote.

Published June 5, 1971.

Black Cultural Center

Afro-Exonian Society (AES) controversies also arose throughout the 1970s, due largely to a proposal for a Black Cultural Center on Exeter’s campus.

In an opinion published Nov. 1971, the Society explained the purpose of such a center.“The Center would attempt to present, in as many ways as possible, the identity of the Black American. Through interaction within the Center a communication of cultural ideals would occur. Hopefully, the Center would also act as a cultural reference point to Black students living in an environment in which their heritage is not represented.”

The Center, and the Society in general, received significant criticism from white students, who took issue with the Society for actively “segregating” the Black and white communities. These criticisms which would continue—in one form or another—throughout the following decades.

The arguments over whether a Black Cultural Center constituted “segregation” spanned over a protracted back-and-forth in the Opinions Section of The Exonian. In a 1971 opinion entitled “Afro-Exonian Intimidation,” Steven Grinton ’72 wrote that “no whites attend the meetings because as one Black student put it, ‘He’d be totally intimidated if he showed up here.’”

“It is this intimidation which has changed the Afro-Exonian Society from an organization to improve the Exeter community into a black bull session. Before the blacks should be given serious consideration,” Grinton continued, “intimidation of white students attending Afro-Exonian meetings should be stopped.”

Conversely, Michael Washington ’76 argued that the Afro Exonian Society was a place for Black students to find comfort in an environment vastly less diverse than some of their hometowns were. “It was only natural for me to associate with other blacks, as I was more comfortable with them, not because I am a racist, but because I grew up among blacks and am naturally more at ease with them. This is not a characteristic peculiar to blacks, it is a human trait, be they the two girls in your English class or the blacks on a college or prep-school campus,” Washington wrote in The Exonian.

Faculty contributed to the pushback against the Cultural Center. “Mr. Hall said, ‘Everybody wants space in that library.’ The limited space in the old library dictates that organizations which cater to only a certain segment of the student population must be considered last,” Grinton wrote in his article.

In response, the Academy’s first Black faculty member, William Bolden, stated that clusters of black students anywhere—in the Society or in the dining halls—could not be categorized as an act of separatism. “I don’t think that those who are visible because they do choose to eat together should be considered representative of the whole number of blacks, when there are others who are not with those groups that you do not take into account. Subconsciously, I think that some black groups choose to [group] together, in a sense, because they do attract the notice of others,” Bolden responded to an Exonian interviewer.

Robert Thompson ’72 argued that the foundation of Afro-Exonian Society rested upon “educat[ing] the white community as to what it is like to be Black.” According to a poll taken by the Afro-Exonian Society on the evening of Oct. 2, 1971, “the need for it is still felt by the blacks here now.”

However, Black students felt uncomfortable sharing “personal matters of blackness with the white community,” Thompson added.

Thompson stressed that the Black Cultural Center provided a locale in which the white and Black communities could interact, a need amplified by the entry of women into the Academy. “If your conscience still fears separation at this point, tell it to answer some questions. What does it want? Does it really believe that an ideal community is one where there is assimilation of backgrounds? Or is a community ideal when racial and ethnic backgrounds are definite and at the point where they can be talked about and, if necessary, reckoned with, to the benefit of everyone?” Thompson asked.

As a result, the Afro-Exonian Society continued to push the proposal to the Academy administration for approval. In June 1971, Craig Kirby ’72, then the newly-elected President of the Afro-Exonian Society, claimed during an Exonian interview that “[it] was the first year [the Black Cultural Center] proposal has been broached to the administration, and that it has, to date, received a favorable reception.” Kirby pledged to push forward with the proposal.

Kirby also suggested in a 1971 open meeting proposals to create a two-semester course dealing with Black history, introduce more third world literature into the English Department and hire ten Black faculty members.

In 1975, a published speech “Myopia and Black Achievement” by English Instructor Dolores T. Kendrick, one of the first and longest serving Black female teachers at the Academy, refuted arguments opposing the Black Cultural Center. “Now, how does a faculty become ‘inspired,’ students become ‘good’ and a will born to ‘achieve and produce success’? Does racial intolerance, the put-down of the Black community, lack of funds, etc., have anything to do with it?”

“[As] our educational environment today becomes more distraught, more frustrated and confused, more destructive and political, [we need] clear vision and care of a concerned administration,” Kendrick wrote. “Without such responsible leadership, we can expect as our society becomes more complicated, uninspired faculty, poor students and apathy.”

Black Identity in The Exonian

Subsequent to Black History Week in Feb., 1974, an exchange concerning the Black identity occurred between two consecutive Exonian issues:

Feb. 20, Issue 32

This issue, published on Black History Week, invited a series of Black students and faculty in the editorial section to speak out about race and racism on campus. Tracing back to the late 1960s, Phil Jeffries ’76 explained that his brother had arrived at Exeter at a time of “black revolution.”

“It was to the black students’ credit that they could unite; it is harder to deal with a united group than with individuals,” Jeffries wrote.

This sense of unity among Black students at the Academy, as expressed through the AES, continued into the 1970s. According to an announcement from the AES in Sept. 1972, the club aimed to ease culture shock for new Black students. Leaders in the Society worked with admissions to review Black student profiles and suggest promising candidates.

Part of this unity, as Sheila Perry ’74 argued, derived from a shared Black culture and their conflicts with racists in the Exeter community. “I constantly get little shocks all through my nervous system when I come in contact with whites on this campus,” Perry wrote. “I feel a small jolt when in English class the word ‘[n-word]’ is used freely by such revered writers as Ernest Hemingway, when a white calls my Afro hairdo ‘electrified,’ or when at the special Black History assembly I heard hisses coming from the back of the hall.”

AES adviser William Bolden contended that the Black Cultural Center was a manifestation of unity and the Black community’s “willingness to exchange ideas” and “avoid... arrogant and futile gestures.”

“Black people are no more likely than any other religious or ethnic groups to march, lockstep, to the commands of a single major figure,” Bolden wrote. “Black students have a willingness to prepare themselves with a superior education for that movement when the media, while they are alive, or historians, after they are dead, may cloak some one of them with the toga of leadership of the black race in the United States.”

In an interview conducted by The Exonian in 1980, Religion Instructor David Daniels, a Black man, voiced his concerns about the Academy as a whole. “Is this community as tranquil as it looks, or is there really a lot of alienation, frustration, and racist attitudes under the surface? Are the black students here really integrated into this community?”

Feb. 27, Issue 33

In the following issue, William McNally ’74 addressed all previous editorials in an op-ed entitled “Black Identity?” “A tone of paranoia seemed to pervade the editorials written by students in the last Exonian... Why is it necessary for blacks to have a specific identity at Exeter? Is it because the black student feels that he can only cling to his culture by joining with his fellows against the pressures of Exeter?” McNally asked.

“One might inquire as to whether blacks at Exeter, by erecting a racial barrier are clinging to a pseudo-culture that has little application to academic life, and creating a social situation which is both unnecessary and destructive to everyone involved. When Sheila Perry says ‘stop making fun of . . . the superficial trappings of my culture,’ does she refer to something real or contrived?” McNally probed.

Published May 12, 1978.

Apartheid and Divestment

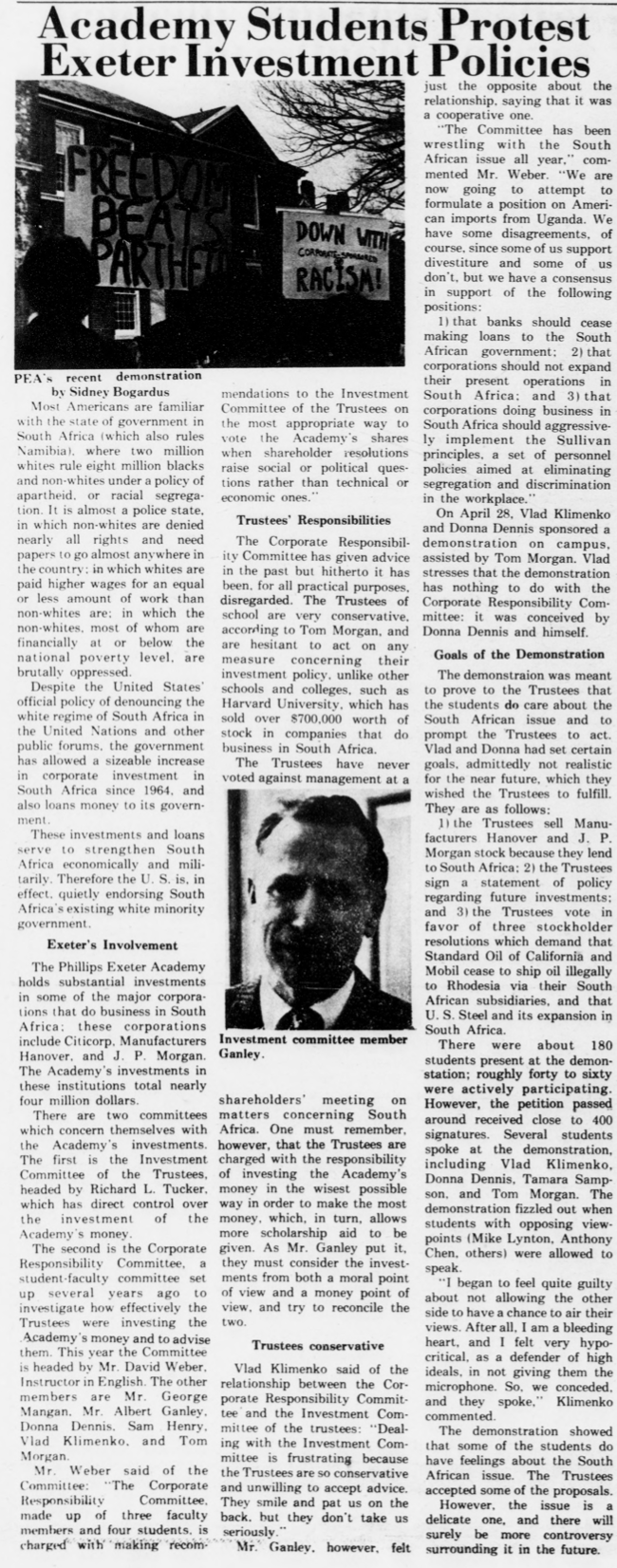

The nation’s attitude on the continued Apartheid in South Africa paralleled that of the Academy—some activists pushed for divestment from the Apartheid regime, while leadership resisted these moves. In 1978, according to The Exonian, the Academy’s investments in South Africa-based corporations amounted to nearly four million dollars. The faculty-student Corporate Responsibility Committee, led by English Instructor David Weber, advised the separate Trustee Investment Committee.

According to Corporate Responsibility Committee member and student Tom Morgan ’79, “The Trustees have never voted against management at a shareholders’ meeting on matters concerning South Africa.” Meanwhile, other schools and colleges, including Harvard University, had sold over $700,000 worth of stock in companies profiting in South Africa.

Vladimir Klimenko ’78, another Corporate Responsibility Committee member, noticed the same resistance from the Trustees. “Dealing with the [Trustee] Investment Committee is frustrating because the Trustees are so conservative and unwilling to accept advice,” he said. “They smile and pat us on the back, but they don’t take us seriously."

History Instructor and Corporate Responsibility Committee member Albert Ganlev, on the other hand, argued that the two committees maintained a cooperative relationship and that the Academy had taken steps in “wrestling with the South African issue.” "As Mr. Ganley put it, [the Trustees] must consider the investments from both a moral point of view and a money point of view, and try to reconcile the two,” The Exonian reported.

The Corporate Responsibility Committee ultimately reached a consensus: “one, that banks should cease making loans to the South African government; two, that corporations should not expand their present operations in South Africa; and three, that corporations doing business in South Africa should aggressively implement the Sullivan principles, a set of personnel policies aimed at eliminating segregation and discrimination in the workplace.”

Morgan urged fellow students to support full divestment in an editorial article in March 1978. “The situation in South Africa is desperate and getting worse,” he said. “A blood bath can and must be avoided. America has too much interest in this area to further divulge itself of influence abroad by allowing this situation to continue and thereby encouraging revolution.”

Dissatisfied by the absence of active opposition to Apartheid, on April 28, 1978, Klimenko, Morgan and fellow Corporate Responsibility Committee student member Donna Dennis organized a demonstration. Klimenko sought to prove “that the students do care about the South African issue.” 180 students attended. A petition, requiring Trustees to: one, divest from multiple companies, including J.P. Morgan and Hanover; two, sign a statement of policy; and three, vote against illegal oil trade, received close to 400 signatures.

Some students criticized a supposed lack of free speech at this protest. In a later issue of The Exonian, published on May 19, 1978, senior Matthew Teplitz ’68 wrote that “what disturbed me most about this demonstration was its atmosphere, rather than its specific proposals. The overzealous nature of the recommendations can be understood, the ‘carnival atmosphere’ cannot.”

“The right to free speech and dissent is one of this nation’s most precious gifts, and yet this demonstration resembled little more than a bastardized pep rally,” Teplitz wrote. “The demonstrators playfully marched around, carrying absurd, and in many cases distasteful signs, and tried constantly to collar passers-by. I got the impression that participation was all that mattered.”

Black Faculty

In June 1971, The Exonian conducted another interview with English Instructor and Admissions Officer William Bolden, the first Black faculty member to be appointed to the Academy. Bolden felt that he was “a token” in the Academy. “There are some faculty here who do not look on me as a teacher, but as a ‘convenience’ which satisfies the school’s unwritten requirement to have someone black on the staff. I’m sure that there are some students here who are not at all sure that I have the qualifications to be a teacher, yet they feel that certainly I have to be here,” he said.

Bolden claimed that Black tokenization extended beyond the Academy itself. “I’m sure that there have been times that I have been trudged out onto a stage in front of people outside the community to show that Exeter does have a black faculty member,” he said.

However, recruitment of Black faculty grew stagnant after the appointment of the first two Black teachers: Bolden and Earl Belton.

Two years subsequent to the interview with Bolden, Modern Languages Instructor Roslyn Grant criticized the Academy’s reticence to hire new Black faculty members. In a Letter to Editors of The Exonian, she wrote, “The Dean of the Faculty states as ‘problems in finding black teachers,’ that black applicants: ‘must sometimes wonder whether Exeter is the happiest of all locations’; ‘find the ‘pressure’ too great’; ‘must resolve the apparent conflict between loyalty to a black community and the professional opportunity Exeter offers’; ‘lack sustaining black companionship at Exeter.’”

“Re-reading that section of the article, I eliminated the word ‘black.’ Those ‘problems’ could apply to applicants in general,” Grant wrote. “Not only have applicants, the few with whom I have spoken, wondered if ‘Exeter is the happiest of all locations’; some teachers have actually decided that in their particular case it is not.”

Grant specifically addressed the state of Black minority among the faculty and its implications on racist attitudes. “How many times since I have been here have I heard: ‘What are single people doing here (at PEA)?’” she wrote. “When a black female was hired one year, the comment of one faculty member was: ‘Oh, that will be good for ____. Now ____ will have somebody to talk with.’”

Coeducation

The seventies also marked the advent of coeducation at the Academy. Women of color did not graduate in 1971, the first class of nine day student females. In 1972, Linda Chen became the first woman of color to graduate, followed in 1973 by Judith Hall Howard, the first Black woman to graduate from Exeter. Hall Howard is spotlighted in Since 1878.

Vietnam

Hostility to new social movements, though present, was not confined to Exeter—it was a feature of the entire Seacoast region, reflected in its press. At the time, publisher William Loeb, mentioned in Since 1878’s 1960s piece, owned what The Exonian described as a “virtual monopoly on the press, the most powerful news media in New Hampshire, having owned both The Manchester Union Leader and the New Hampshire Sunday Post.”

Loeb was known for making use of incendiary and often racist rhetoric in the pages of the Union-Leader. An opinion in The Exonian, published March 1972, quoted a particular op-ed from Loeb entitled “Hanoi’s Little Helpers.” Loeb’s piece had been written amid 1969 anti-war protests in the Seacoast area: “Attention all peace marchers: Hippies, Yippies, Beatniks, Peaceniks, yellow-bellies, Commies, and their agents and dupes. Help keep our city clean, just by staying out of it. The Editors.”

Exeter students, however, were heavily involved in protest movements against the War. For instance, a combined 400 students from the Academy and Exeter High School gathered on Oct. 15, 1969, involving the tolling of church bells, vows of silence and silent protest. The purpose of the protest, according to the Moratorium’s organizational statement, was “to bear solemn witness against American involvement in the Vietnam War.”

Several attempts were made by anti-war groups on campus to replicate the Moratorium and similar protests from the 1960s, to varying effects. Some protests fell through, like one attempt in April 1972, organized under the leadership of then-upper Mike Hoffheimer. Hoffheimer had planned what would have been a “massive turnout” on April 29, 1972. He observed, however, that “no one want[ed] to strike” and instead formed a Student-Faculty Council to form a series of discussions and seminars on the war, attended by over 100 students.

On April 29, The Exonian’s opinions pages published two conflicting articles, one expressing support for student-led strikes and another expressing opposition. Hoffheimer wrote in favor of the strikes. “We cannot speak against the war while showing Nixon that we are going to increase our output,” Hoffheimer wrote. “The time for planting flowers arranged as peace signs is over. Our constructive protests, our songs, our art, our poetry have hit deaf ears. We are no longer asking, we are demanding that Nixon get us out now.”

The piece against protests, written by an anonymous student under pen name “AJG,” argued that, at least among boys at Exeter, few students understood the details of the war by the seventies. “Attitudes of Exeter students have changed since the war issue was supposedly ‘put to sleep’ when Nixon began de-escalating the war, Vietnam has been sliding out of the public view, leaving some uninformed students unaware of our situation there.” he wrote.

“The student body has also been stratified by coeducation,” the anonymous student continued. “Many students, a majority of the girls, perhaps know something of what is happening in Vietnam but still do not care what the impact of these events is. If a general strike or a protest demonstration were called for now, these students could not be counted on to back it.”

Little discussion occurred in The Exonian about the disproportionate impact of the war on Black people. However, a piece in the April 3, 1971 issue of The Exonian connected the war to anti-Black racism in the United States and the activism of the late Martin Luther King Jr. The piece’s author, writing under the initials “EML,” wrote, “One of [King’s] dreams was to end this war. He envisioned this dream in 1968, a dream he never lived to see achieved. But now, three years later, on the day commemorating his death, we are reminded that King’s dream is still only a dream.”

The piece went on to note the racial dynamics of casualties. “Over 25,000 blacks,” they wrote, “have already been killed in Vietnam to date, representing over 55 percent of all American casualties in this war, but only 16 percent of the whole population of this country is black.” The student called upon Congress to “end this bloody, racist war.”

In spite of anti-war movements on campus, several students expressed that the decade was marked by apathy to the War. Following a series of protests, seminars and hunger strikes on campus in May 1972, one organizer took to The Exonian to express disappointment at turnout. Phillip R. Van Buren ’74 wrote, “Despite a contrary attitude floating about campus, I believe that last Thursday’s anti-war activities were very much a failure, or at least they were nowhere near as politically significant as they could have been. This failure was largely due to a lack of drastic action.”

“And the frustrating question is how to achieve a drastic protest in such an apathetic place as Exeter,” Van Buren continued. “At times we have the energy for it, but it seems we never have the organization. This energy comes in a wave of emotional drive, that lies behind all Exeter student activism, but it needs to be caught at its crest and channeled into some meaningful action.”

A student, then-lower Dale Siner ’74, offered a response in a June 2 issue of The Exonian. It is printed below in full:

Phillip Van Buren stated in the May 10 Exonian that the reason very few students attended last Saturday’s protest demonstration was that the student body as a whole was afflicted with mass apathy. “Most of the students don’t give a damn,” he generalized. Mr. Van Buren apparently thinks that all students must share his political beliefs. Did it ever occur to him that the majority of the students who as patriotic citizens refused to protest believe that for the most part Mr. Nixon’s policies are in the best interests of the United States? Although the bombing of North Vietnam is wantonly destructive and brutal, the blockade is a move necessary to cut off Russian supplies and give the South Vietnamese civilians relief from the North Vietnamese onslaught. I urge the left-wing faction of this Academy to leave others of a less radical political stance to their own beliefs and not make them feel obligated to join in their actions and ideology.

Kent State Shooting

On May 4, 1970, twenty-eight National Guard Soldiers shot thirteen unarmed Kent State University students at a peace rally against increased efforts in the Vietnam War. In light of the detonation of the Vietnam tinderbox, the AES declared in The Exonian its endorsement of all efforts seeking to create social reform.

“We see the issue of Kent State as indicative of a long standing social illness, the roots of which have been manifest in: lynchings, race riots, KKK terrorism and the systematic economic exploitation, political disenfranchisement and social ostracism of our people,” the Society wrote. “We as black people have had long experience in attempting to correct this illness. We have come to realize that social change cannot be effected in a day or in a week, nor by a short range, emotional commitment… We urge you to maintain your attitude towards the achievement of justice in this country as you begin to take on real positions of political and economic power.”

“In light of the superior forces of the establishment, we have realized that direct confrontations are suicidal,” AES concluded. “Individual instances of social injustice are not isolated, but must be seen in the light of the total social reality.”